A couple years ago I was speaking with a tenure-track professor in Kinesiology at another institution, telling her how excited I was about conducting qualitative research about aesthetic competence.

“Can I give you a piece of advice?” she said.

Oh boy. No, but, “Of course!” I said.

“Don’t do qualitative research.”

The professor went on to explain that qualitative research is not funded as abundantly as quantitative research, and while she’s not wrong, my motivation for research has little, if anything, to do with money. Shouldn’t we be motivated by our philosophical assumptions, our passions, and the best way to answer a question?

Certainly, but at the same time I acknowledge that someone has got to pay for all this science. Sometimes it’s easier to conceptualize the value of highly technical work or statistical analyses that can provide a more generalizable result. But regardless of whether I’m performing biomedical feedback and force plate analysis on dancers jumping or sitting with a dancer in an empty room asking her, “how does it feel when you jump,” it’s all science.

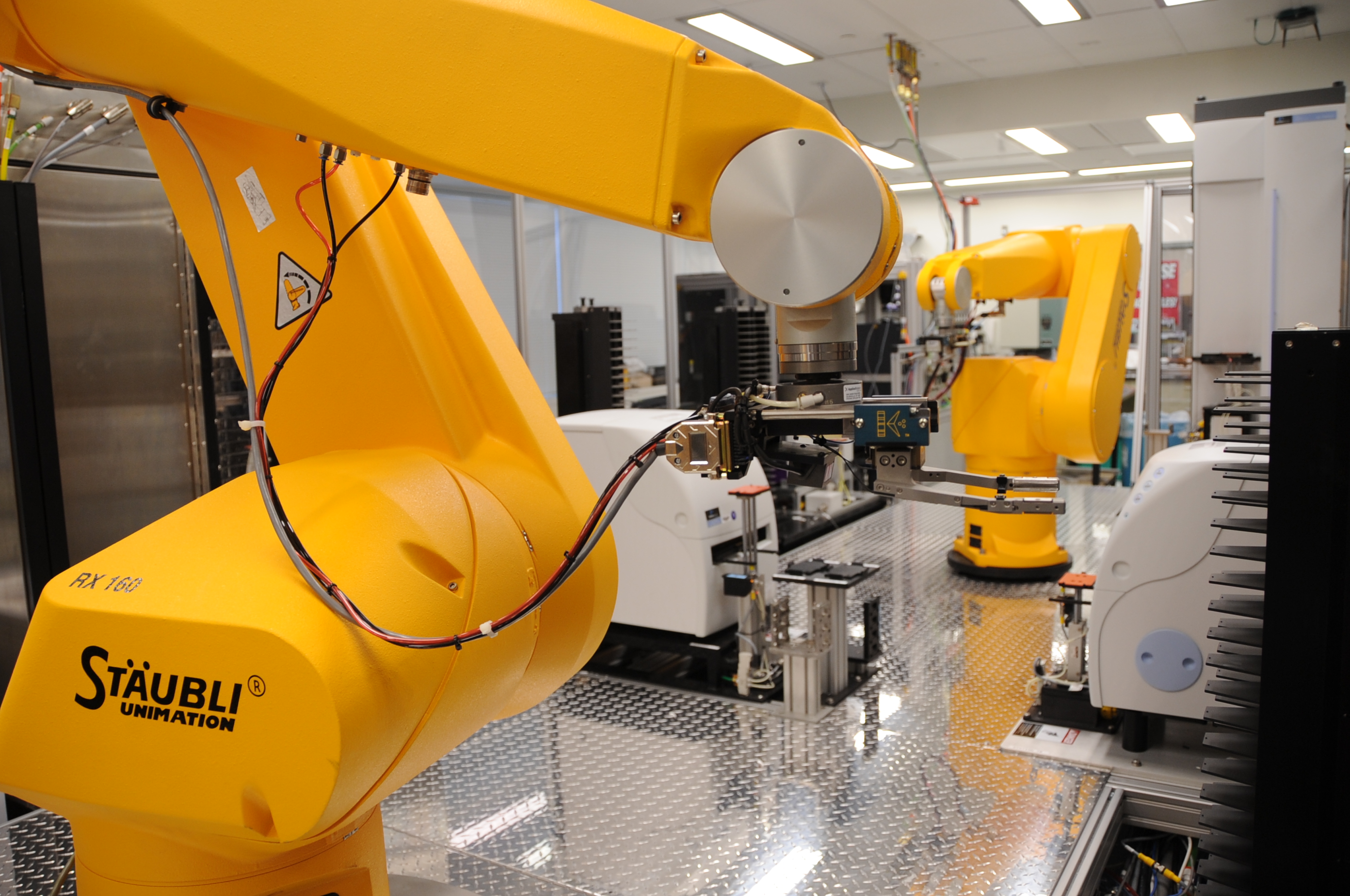

This is science.

and this is science.

While quantitative and qualitative researchers might not always get along, we have a number of shared values that reach to the core definition of research.

Responsible conduct in research is built on a number of key values:

honesty

accuracy

efficiency

and objectivity.

Basically, we agree to convey information as truthfully and correctly as possible, honoring the commitments of time, money, and individuals with the goal of advancing knowledge and putting that knowledge to work. The expression of these values varies from question to question and researcher to researcher. Certain work is more focused on advancing knowledge than application (or vice-versa), but generally speaking, this is every researcher’s goal.

The level of trust that has characterized science and its relationship with society has contributed to a period of unparalleled scientific productivity. But this trust will endure only if the scientific community devotes itself to exemplifying and transmitting the values associated with ethical scientific conduct.

~National Academy of Sciences, 1995

People believe science, whether it’s good science or not. So, we have a responsibility to conduct ourselves as honestly and ethically as possible. It can sometimes get confusing when popular news media, or CrossFitters, get their hands on science. It can lead to broad assumptions about bacon causing cancer or stretching causing injury. It’s up to us as a unified front to manage the expectations, assumptions, and slow but important progress made in all types of investigative and descriptive research… money or no money.